|

W |

“Why don’t |

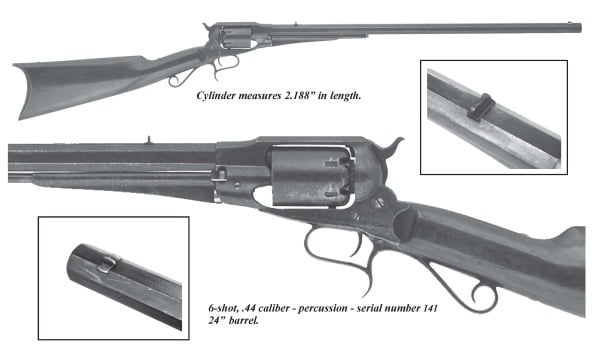

Remington Percussion Revolving Rifle serial number 141

|

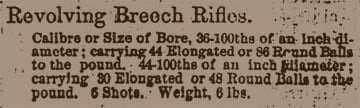

It was |

A second reference found about the Remington Revolv- |

| Page 26 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

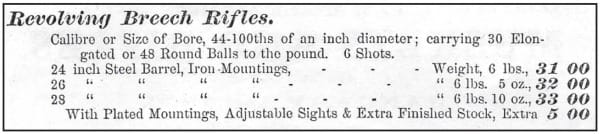

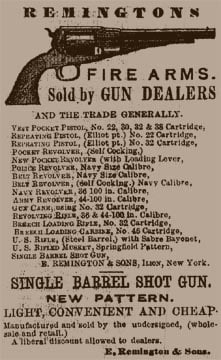

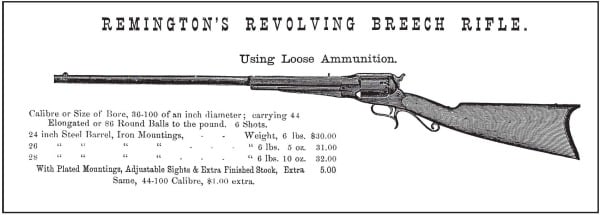

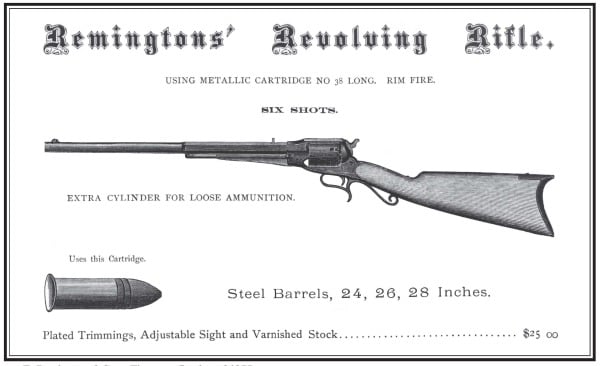

The following, in chronological order, are other advertisements that list the Remington Revolving Rifle:

|

|

| Page 27 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

|

got me started looking into the ad’s, and the one that I

With the above information in mind, the last advertisement by Remington for the Revolving Rifle being in 1879, I find it easy to assume that final sales would have been in 1879 or shortly thereafter. |

| Page 28 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

One of my research goals for the future is to gather information from various firearms distributor and dealer records that show

purchase and sale of the Remington Revolving Rifle, hoping that this might aid in clarifying production dates. Input by readers

toward this goal is encouraged.

While being briefly mentioned in various collectors’ price guides, in one or two magazine articles, and consuming a scant

quarter page in Edsall James book ‘The Revolver Rifle” published in 1974, my survey over the last several years has produced a

great deal of information concerning the Remington Revolving Rifle. And while this information answers several of the questions

I had, it also proved false, some previously published information, as well as raising many new questions. Most of these questions

relate to physical characteristics so I’ll address them a bit later in this article.

No doubt it’s obvious to most that the patents associated with the Revolving Rifle are the same as those associated with the

following firearms. The Remington-Beals Army/Navy Revolver, The Remington Old Model Army/Navy Revolver, and the Reming-

ton New Model Army/Navy Revolver. These patent numbers and dates are:

‘ U.S. Patent #21,478 for the Beals Revolver; dated September 14, 1858

‘ U.S. Patent #33,932 for the Old Model Revolver; dated December 17, 1861

‘ U.S. Patent #37,921 for the New Model Revolver; dated March 17, 1863

PHYSICAL PROPERTIES

The following information, while not etched in concrete, is based on information gleaned from approximately 60 survey forms

submitted by owners of Remington Revolving Rifles in the U. S., Canada and Europe. Included in this study, are the guns in my own

collection, which have been disassembled and examined closely, allowing me to state that the information received from other

collectors does not vary greatly from the information concerning my guns.

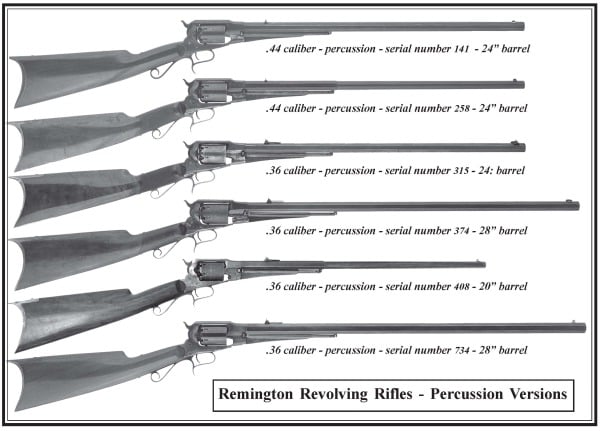

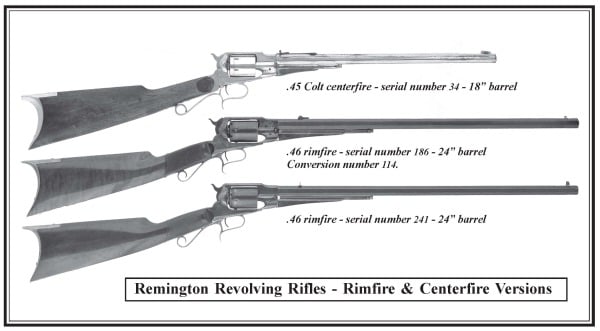

The Remington Revolving Rifle was initially produced in percussion models in two basic sizes, related to caliber. Both of these

sizes were later offered in rimfire cartridge models as well. These initial sizes were the .36 cal percussion cap & ball, and the .44 cal

percussion cap & ball. The cartridge conversions later offered were the .38 long rimfire and the .46 rimfire.

| Page 29 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

The capping plate conversion model utilizes the same design as on both the .38 and the .46 models.

Approximately one-third (17 of 56) of the rifles surveyed were of the larger caliber. Either .44 percussion or .46 rimfire, with

three of these 17 examples identified as being ‘non-factory” modified to accept .44 or .45 or .46 rimfire cartridges. Of the remain-

ing 14 large bore models, 9 rifles in the study group are identified as being .44 percussion, and five are verified to be .46 cal.

capping plate conversions. This .46 rimfire model was by far the scarcest, but as time goes on, more of these come to light.

Of the small bore models, numbers indicate that the ratio between percussion and cartridge model is approximately 50-50,

with 20 being .38 rimfire cartridge models and 19 being .36 cal percussion models.

All of the advertisements I’ve seen show the Remington Revolving Rifle as having a part hexagon, part round barrel. This

barrel type is, by far, the most scarce of the two barrel styles. The full octogon barrel represents approximately 90% of the rifles

reported.

Barrel lengths were well represented in the advertised 24″, 26″, and 28″ lengths, showing no pattern by serial number

sequence, caliber, or type of mountings. There were, however, two guns each that had barrel lengths listed at 30″ and 22″. I

personally inspected one of each of those and am satisfied that they both are factory guns. Both of the 22″ barrels were part

round part octagon, while both 30″ barrels were full octagon.

Barrel diameter, or the dimension across the flats, shows a vast majority in both calibers to be 3/4″ with a few measuring 11/16″ and a few measuring 13/16″. Most of the 13/16″ barrels, and at least one of the 3/4″ barrels, had a channel undercut on the bottom flat to allow proper seating of the loading lever without having to modify the link of the same.

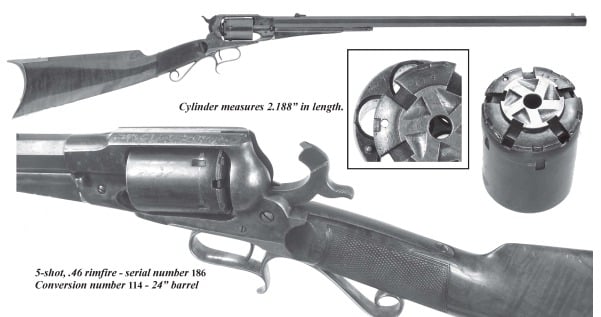

While it is common to think that the cylinder length of 2-3/16″ is a quick way to determine if a particular firearm is factory

original, and it is a fact that 95% of those guns surveyed did in fact have this length cylinder, there are a couple of guns out

there with 1-15/16″ cylinders that I’d like to have a closer look at, because everything else in their survey forms indicates that

they are factory-produced guns. If we are to believe that the Remington factory did supply this rifle with the 1.9375″ cylinder,

then the frame design will also vary based on the length of the cylinder. Maybe Remington put out a few with 1.9375″ cylinders

during material shortages? If so, how did they decide which frame they would use. Would they have modified an existing

handgun frame to accept the stock, or would they have produced frames to fit a 1.9375″ cylinder?

All of the factory guns I’ve looked at that are .36 percussion, .44 percussion or .38 rimfire have 6-shot cylinders. One that I

own and others that I have surveyed appear to be a gunsmiths’ modification utilizing a bored thru cylinder and are 6-shot.

| Page 30 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

The rear of that cylinder doesn’t leave much skin between the holes, leading me to believe that for safety reasons, Remington

limited the large bore models to 5 shots. All of the .46 rimfire capping plate style cylinders surveyed to date are 5-shot.

While all of the loading levers on factory rifles are 7 inches long overall, I have seen a few examples where the web is less

than the normal 5 inches long, and the rod may be pieced together from two lengths. This may be as the result of a repair during

the life of the gun, but I doubt that it left the factory that way. I have also seen loading levers on apparent gunsmith rifles that

are of the same length and design as used on Remington handguns.

I have seen a number of obvious gunsmith modifications to handguns (adding barrels of various lengths; a shoulder stock;

etc.) that use the normal handgun loading lever, frame, and cylinder.

| Page 31 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

While all of the factory stocks that I’ve measured come in at 14″ with the same shape and

length of pull, close inspection of the stock on these gunsmith modification firearms show slight deviations from the factory

shape. Examine closely the example where the stock meets the frame. You’ll notice the length of the concave area, forming the

transition from the frame to the body of the stock. Now look at the example which is the Remington factory stock and you’ll see

a transition area of much smaller size.

The Remington Revolving Rifle was configured in variations, with a choice of front and rear sights, choice of wood grade

and finish, choice of iron or plated mountings, choice of caliber, choice of barrel length, and it was offered in an engraved model

as well, although not mentioned in any catalog or price list.

While the front sight offering appears to have been limited to a short blade, a long blade and a bead, rifles with the Beach

Combination Globe front sight do exist. Most of these examples appear to be those ordered with all of the options that were

offered at that time.

Rear sight variations have been noted as a fixed buckhorn sporting sight graduated for 50-300 yards, and two different

lengths of adjustable folding leaf sights.

The stock could be ordered in plain, or fancy, smooth or checked, oiled or varnished configurations. The fancy grade, with

checking and varnish is a very nice looking work of wood.

While plated mountings did cost extra at various points in its offering, most of the rifles surveyed did have them. Iron

trigger guards and butt plates are the exception rather than the rule.

.

Engraved rifles are very rare, with only two being surveyed. As was normal for Remington in that time period as well as is

the practice today, the engraving work is top quality. In addition to the engraving shown on rifle serial number 315, other areas

on the rifle that were engraved include the muzzle end of the barrel surrounding the front sight, as well as total coverage of both

pieces of the two-piece butt plate.

While at first glance, the trigger guard appears to be the same in shape on all models, a closer inspection reveals that there

are a possible four different models of trigger guard. These vary in the manner and number of attaching screws required to be

used. This variation has an effect on the frame as well, in that it is modified to match the trigger guard attaching screws. My

opinion is that each of the design changes, which resulted in an additional screw being used to attach the trigger guard,

increased the strength of the trigger guard.

The one screw trigger guard consists of a mounting plate with a tang on the rear that slides into a recessed area of the

frame, and a single machine screw holds the mounting plate and the frame together. The scroll portion of the trigger guard has a

threaded stud on the upper front area of the trigger guard which screws into the mounting plate. At the rear of the scroll assem-

bly, there is a single hole through which a wood screw is used to secure the assembly to the stock.

| Page 32 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

The two screw trigger guard, as reported by three different revolving rifle owners, has a screw at the front that attaches to

the frame, and a screw at the rear that attaches to the stock. As yet, I do not have a photo of this model, but when I do get one,

I’ll pay close attention to see if it’s really a three screw model.

The three screw trigger guard is similar to the two screw model in that it uses a screw at the front and the rear of the guard,

but a third screw has been added that is installed thru the left side of the frame, thru the guard and threaded into the right side of

the frame. This screw is located just to the rear of the finger opening in the trigger guard. If I’m correct in my assumption

concerning the two screw trigger guard, as well as my suspicion that the one screw models are gunsmiths modifications, then I’ll

feel comfortable in saying that the Remington factory only produced the Revolving rifle in the three screw and four screw

variations.

| Page 33 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

The four screw trigger guard uses the two primary screws, at the

front and rear of the assembly, with two additional screws, one each on the under left

and under right side of the guard, just to the rear of the finger opening in the trigger guard.

These two screws thread upward into the underside of the frame. As is the case with most variations, there is no consistency

based on serial number sequence.

The frame also has a variation, in the manner of what appears to be a vent or flash hole in the sight channel on the top of

the frame. Some rifles have this, some don’t and there is no consistency based on serial number sequence. I don’t know the

significance of this hole, and would like to hear from someone who has information on this design feature.

While all of the iron butt-plates that I have viewed are of the one piece variety, the brass butt-plate has been noted in both

one and two piece style. The one piece variety has a much more pronounced flat edge at the rear most edge of the upper curve

than does the two piece butt plate. The two piece style has a shaped flat piece, inlaid into the bottom of the stock, and held in

place with two additional screws. The lower edge of the curved rear of the two piece butt plate overlaps the rear of the bottom

piece, further strengthening the attachment.

Markings on the Revolving Rifle are similar in nearly all rifles surveyed. Barrel markings, if present, read breech to muzzle, in

three lines, all capital letters:

PATENTED SEPTEMBER 14, 1858

E. REMINGTON & SONS ILION, NEW YORK, U.S.A.

NEW-MODEL

While caliber markings in non-typical locations are seen, they are not all that common. Remington incorporated the caliber

marking within the engraved model .36 caliber, and the plain stamping for the iron mounting model .44 caliber.

5-shot, .46 rimfire – serial number 186

Conversion number 114 – 24″ barrel

| Page 34 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

Serial numbers are found in some if not all of the follow-

ing locations:

- On the cylinder pin either on the flat of the wings or on the rod.

- On the stock in the tang recess area.

- On the trigger guard and frame tangs covered by the stock.

- Inside the one piece butt plate, very lightly stamped.

- Inside each piece of the two piece butt plate, very lightly stamped.

- On the exterior of the trigger guard near the rear mount- ing hole.

- On the face of the cylinder, with the conversion model carrying the number of the rifle as well as the number of the conversion.

- On the bottom flat of the barrel, under or near the loading lever.

- On the underside of the rear tang of the one piece trigger guard attaching plate.

- On the underside of the rear attaching flat of the one piece trigger guard.

OPINIONS

While being able to only estimate the number

of Revolving Rifles produced, I think the published information in most price guides is relatively

accurate. With the highest serial number

recorded being number 738, and the

lowest number recorded being number 10, with the

exception of one rifle listed in “The Guns

of Remington” as being without serial number and

possibly being a prototype, my opinion is that approximately

800 of these rifles were produced. One quirk in this reasoning

is that to date, I have not received any information for a rifle

with a serial number that falls in 600 to 699 range. I find that

unusual, in that all other ranges are well represented.

Sometimes I wonder if there was a time where none of these

rifles were produced and if records were not available to

determine the exact last number used, a decision was made to

start again, but high enough to insure that no duplicate

numbers were used. Possibly, records will be unearthed that

reveal an export order for 100 of these rifles? At other times I

dream that maybe these missing 100 serial numbered rifles are

just sitting in a warehouse, waiting to be discovered.

What was the most common configuration encountered?

The .38 rimfire conversion, with a 24″ octagon barrel, small

blade front sight, buckhorn rear sight, and a two piece butt

plate, on a standard grade stock.

What was the least common configuration encountered?

The engraved model in any configuration is the most rare.

The scarcest by caliber is the .46 rimfire, while the 28″ and

30″ barrel models were rare as well. By far, most unusual is

any of these rifles in a condition of 90% or better, with only

one being recorded at above 95%. It appears to me that with

such a low cost rifle, produced in such low numbers, and

with such a limited appeal, not much care was taken to insure

their condition lasted. I have seen a number of examples that

have fallen victim to black powder corrosion, as well as other

indicators of hard use during their lifetime. The most extreme

example I’ve seen, is also one of the scarcest. On this page is

of what remains of a .46 rimfire capping plate conversion

model.

Giving thought to the decision of E. Remington & Sons

to produce the Revolving Rifle, I think that this might be one

of those cases where the product was built, and then an

attempt was made to create a market. Realizing that the Civil

War, (‘The War of Northern Aggression”) was ending, not

only would military spending come to a halt, but there would

be a glut of

firearms, particu-

larly handguns

available for

personal use, so if

any firearms

would be sold,

they would have

to be targeted to

the public, be an

improvement over existing

models, be able to be produced inexpen-

sively, must be able to hit the market

rapidly, and utilize existing tooling and

experienced personnel as much as possible.

To accomplish all of this, E. Remington & Sons

could use existing tooling, capitalize on the excellent reputa-

tion that its handguns had gained, utilize existing inventory

and personnel, and immediately begin production on a

firearm that families could use in hunting small to medium size

game. Combine this with the fact that Remington needed to

enter the civilian long arm marketplace. Don’t forget that at

this same time, Remington was introducing the Beals single

shot rifle, and we can all see the similarity in the barrels and

stocks used on both rifles.

Why didn’t Remington’s revolving rifle succeed? Why

did production stop? My opinion is that with the marginal

design and it being a low power rifle, serious hunters weren’t

interested in it. Combine that with Winchester’s new lever

action repeater coming onto the scene, along with

Remington’s major emphasis going into producing the

rolling block military and civilian rifles, this product just

wasn’t one that could succeed.

| Page 35 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

Where do I plan to take this study from here?

Still harboring a high level of interest that I had when I started this project, my immediate plans are to continue gathering

information by way of my survey form, and conduct a statistical analysis of the data. My hopes are that with professional help

in that arena, mathematics will give us a more accurate picture of the how’s and why’s of the production of this rifle. My mid-

range plans include completing a project that I have started which is to compile a complete set of scaled drawings of all of the

component parts of the rifle. This could take the better part of another year of available spare time. My dreams are probably no

different than many of yours in that I’d like my grandkids to have a copy of my book on Remington Revolving Rifles on their

bookshelf.

A big debt of gratitude goes out to the late Leon Wier Jr., our Journal Editor, Roy Marcot, RSA Past President Fritz Beahr,

and other RSA members for all of their help getting me started… helping me over hurdles along the way… and for sharing files

and photos that they had gathered over the years… and special thanks to Joe Poyer for his magnificent photography.

Mike Strietbeck

| Page 36 | 2nd Quarter 2007 |

| On-line Search/Sort Journal Index |

On-line Journal Articles New Journals have links to

|